Chimanimani National Park, located in Sussundenga district, Manica province, concluded on 10 December a five-year cycle (2021–2025) of implementation of the Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development Project (CBDC), financed by the French Development Agency (AFD), the French Global Environment Facility (FFEM) and Fauna & Flora (FF), with a total budget of 4.8 million Euros. The final results workshop brought together implementing partners, local government, communities and specialists to validate achievements that include the documentation of 1,365 biodiversity species, the enhancement of 9 tourism sites with historical and cultural potential, and the design of innovative financing mechanisms based on ecosystem services.

Published at 19/12/2025

Chimanimani: 5 years of concrete results in biodiversity conservation and community development

Chimanimani is one of Mozambique’s 57 Important Plant Areas and one of the main water providers in the region, feeding the Buzi river basin, which supplies more than one million people in three districts of Manica province and provides around 70% of the water that reaches the Chicamba dam. Before the project, knowledge about biodiversity was fragmented, cultural heritage was poorly documented, and local communities lacked development models compatible with conservation. The CBDC was designed to respond to these gaps through an integrated approach that combines conservation, community livelihoods and territorial governance.

The main tangible result of Component 1 was the creation of a consolidated database with 1,365 flora and fauna species recorded in Chimanimani National Park and its buffer zone. This scientific advance was articulated with local community knowledge, through an ethnobotanical study conducted by IIAM that highlighted traditional uses of medicinal, food, spiritual and artisanal species.

Component 1 also included a biodiversity and cultural-heritage inventory, which led to the identification of 33 sites: 8 mountains, 4 sacred forests, 16 waterfalls/lagoons/springs and 5 archaeological sites. This process resulted in inventory and cultural-heritage management manuals, a code of conduct for visitors in three languages, and a 10-year marketing plan. Based on this work, 9 sites were selected for tourism development, creating new opportunities for income generation linked to culture and nature.

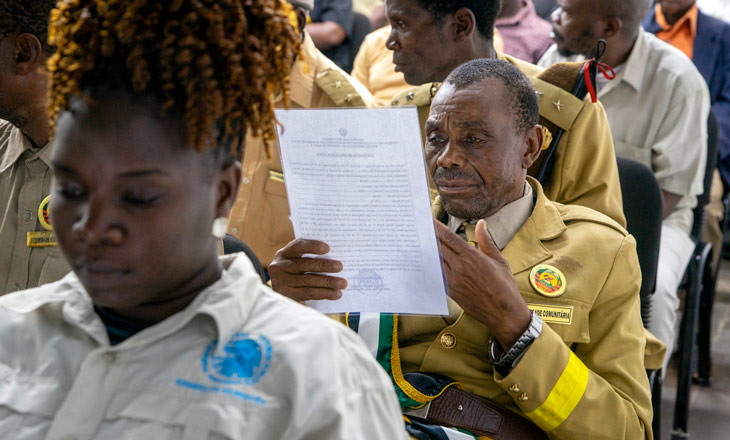

In Component 2, the focus was on clarifying land rights and strengthening community inclusion. Community lands were demarcated, community Land Use Plans were developed, 20 community associations and 20 management units were formally established, and more than 5,000 household plots were demarcated. According to Clara Levy, from AFD,

“land and community governance has been considerably strengthened, more than 5,000 plots have been demarcated, 20 associations have been legally established, and we were pleased to see greater participation of women and young people in the processes,” adding that “this dynamic is important or even essential to ensure sustainable management of resources and a real and inclusive ownership of new opportunities.”

Component 3 consolidated the honey value chain and other natural products, transforming a traditional activity into an organised economic opportunity. Lead beekeepers were trained, the processing facility was rehabilitated, and a new range of products under a local brand was created, strengthening the link between forest conservation and increased household income.

Finally, Component 4 addressed the major challenge of financial sustainability. BIOFUND led Payment for Environmental Services (PES) studies that estimate the value of water-related ecosystem services provided by Chimanimani National Park at around 4 billion meticais per year (about 63 million USD), equivalent to several decades of the park’s operational costs. As highlighted by Vanda Machava, from BIOFUND,

“Chimanimani National Park provides different services. For example, we know that part of the population depends on agriculture. They obtain water from the different rivers that originate in Chimanimani National Park. This water is also used for domestic consumption, for fisheries and mini-hydropower plants also produce energy using this water,” reinforcing that water is a direct link between conservation and human well-being.

Within this component, the project also emphasised capacity building in the Park for the implementation of restoration projects aimed at achieving net biodiversity gains. It restored 240 hectares, created 78 temporary jobs for community members living in the buffer zone, and trained 3 park technicians in degraded-area restoration.

The end of the project was not presented as a final point, but as a transition. In the words of Clara Levy, “As we reach the formal end of the project, I would like to remind everyone that this does not mean the end of our collective commitment. On the contrary, this closure marks the beginning of a new dynamic.” The call was echoed by Contardo Muarramuassa, who stated: “Chimanimane is our hope. All of us must, with one voice, conserve this heritage, because we depend on it for our very existence,” capturing the essence of the CBDC: conservation as a shared responsibility and a condition for the future of communities and of the country.